Asynchronous Web Scraping

Web-scraping, in many projects I worked on, has been a time-consuming process. In this article, I share my recent experience of achieving 10x boost in the web-scraping speed using Python’s lesser-known asynchronous paradigm.

Motivation

If you’re not a soccer fan, you can skip this and proceed to the next section. In the recently concluded club football transfer window, the ‘transfer triangle’ deal involving Arsenal’s Giroud, Borussia Dortmund’s Aubameyang and Chelsea’s Batshuayi intrigued me. This got me started on a personal project to find if such transfers can be explained/predicted using player ratings (I know a player’s transfer between clubs is influenced by a range of factors but no harm in building a naive model). To execute this analysis, I had planned to collect FIFA gameplay ratings of currently active men football players from sofifa.com.

Issues with Web Scraping

To start with, the data of interest was housed across several pages on sofifa.com. In total, there were over 18,000 pages to scrape, which can be divided into two categories

- Pages with tabular data with the list of players and URLs to their pages

- Individual player pages, each with 80+ personal and gameplay attributes

A simple Python script, using the requests library, was able to get the first set of pages in 4 mins. On average, it took 1 sec to download and process one page. This meant I require 5 hrs (18000 sec) to download the remaining pages. First, this runtime is insanely high for the amount of data I was extracting. Second, even if I decide to run my script for so long, no sane web admin would return valid HTML pages after their preset threshold on the number of requests from an IP is exceeded. In short, the two challenges I was facing were

- high run time

- large number of requests.

Using asynchronous functionality of python, I was able to achieve the task of downloading all 18,000 pages in 30 minutes.

Synchronous vs Asynchronous Execution 10000ft Overview

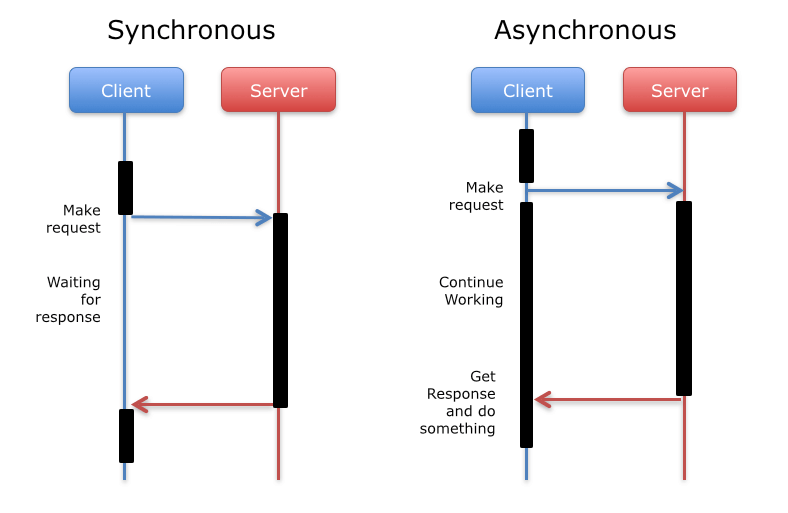

Programs in which code is executed sequentially are synchronous. Such programs call a function and wait for the function to return a response before executing next command. On the other hand, asynchronous programs call a function and continue to execute next command instead of waiting for a response. Once a response is available for the previously called function, the program goes back to that function call and processes the response. In short, asynchronous execution can be seen as a way of task switching that minimizes idle time.

An analogy for synchronous vs asynchronous programs would be a case where I plan to communicate with my good friend Jay. Calling Jay on a phone is synchronous while communicating over an email is asynchronous. Over a phone, I first key in Jay’s number and wait for him to pick up. Once he picks the call, I say something and wait for him to respond. If you consider me as a program, I wait for the server (Jay, in this case) to return a response before executing my next command (say something). This is how a typical synchronous program works. If I choose to communicate over an email, once I draft and send the email, instead of waiting for a response, I get on with my work. This is an example of an asynchronous program, where the program continues executing other tasks instead of waiting for a response.

Asynchronous Programming in Python

There are several packages in Python for doing asynchronous programming. One of these packages is asyncio, which is a standard library added in Python 3.4. Under the hood, asyncio uses event loops, coroutines, and tasks to minimize idle time. Curious readers can refer to this post for details on how things work. Another library that goes hand in hand with asyncio is aiohttp that creates HTTP client/server sessions for asyncio. I overcame the second hurdle of requesting a large number of pages by creating an HTTP client session.

import asyncio

import aiohttp

import requests

async def _fetch(session, url):

async with session.get(url, timeout=60 * 60) as response:

return await response.text()

async def _fetch_all(session, urls, loop):

results = await asyncio.gather(

*[_fetch(session, url) for url in urls],

return_exceptions=True

)

return results

def _get_htmls(urls):

headers = {'User-Agent': 'Mozilla/5.0 (Macintosh; Intel Mac OS X 10_11_5) AppleWebKit/537.36 (KHTML, like Gecko) Chrome/50.0.2661.102 Safari/537.36'}

if len(urls) > 1:

loop = asyncio.get_event_loop()

connector = aiohttp.TCPConnector(limit=100)

with aiohttp.ClientSession(loop=loop, connector=connector) as session:

htmls = loop.run_until_complete(_fetch_all(session, urls, loop))

raw_result = pd.DataFrame({'url':urls, 'html':htmls})

else:

raw_result = {urls[0]: requests.get(urls[0], headers=headers).text}

return raw_result

Above script has functions that take in a list of URLs and return a dictionary with URLs as keys and the HTML response returned by the web server as values. I recommend reading this blog to fully understand the snippet. (Note - This code works well with asyncio version 3.4.3 and aiohttp version 2.3.9 but breaks on18th line for newer versions.)

Note: This crawler hits web-server multiple times each second and can have detrimental effects on under-powered sites. Scrape Responsibly.

References

- https://hackernoon.com/asynchronous-python-45df84b82434

- https://medium.freecodecamp.org/a-guide-to-asynchronous-programming-in-python-with-asyncio-232e2afa44f6

- https://stackoverflow.com/questions/10102580/how-does-synchronous-and-asynchronous-communication-work-exactly/10102768#10102768

- http://ntoll.org/article/asyncio